Of Contracts and Photographers

(This is a guest post from Isaiah Brookshire, a writer, photographer, and globally-focused multimedia storyteller specializing in cultural and humanitarian storytelling. You can learn more about him on his website: www.isaiahbrookshire.com)

When an NGO hires a freelance photographer, usually the photographer will present the NGO with a contract detailing things like licenses, copyright, usage, etc. But unless your have a background in commercial media, some of terms can be confusing. Today I want to talk about my experience presenting non-profits with contracts and discuss some of the terms that cause the most confusion.

Before I go any further I should mention that I’m not a lawyer and this doesn’t constitute legal advice. Even though I once thought about becoming an attorney (and then decided I just wouldn’t know what to do with all that money), all I can offer is stories from my personal experience. I should also note that this isn’t a comprehensive list of terms you might find in photography contracts, just a starting place.

Wait, am I buying these photos?

Getting photos from photographers is simple; they take the photos, you pay for them, and then those photos are yours to do with as you like. Sound good? I’m afraid not. With some photographers this might be the case but with the majority of professional photographers, you will find that what you are paying for isn’t the photo but a license to use it.

“Hold on, I just flew a photographer halfway around the world to shoot for my organization and the photos aren’t even mine?” Yep, in most cases the photographer will retain the copyright on the photos and only license them to your organization. (Side note: there is such a thing as a copyright buyout where photographers sell their images lock, stock, and barrel, but these can be very, very expensive.)

Okay, so what is a license?

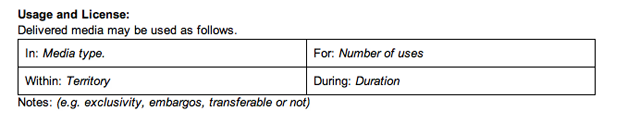

A license (in the photography sense) basically sets out the conditions under which an image can be used. The usage and license section of my basic contract looks like this:

This part of my contract provides my clients with five important pieces of information:

- How they can use my images

- How many times they can use my images

- Where (geographically) they can use my images

- How long they can use my images

- The notes section allows me to grant further rights or put more stipulations on usage

Most photography contracts should provide similar information (though they may use different terms and look very different). From here I want to talk about each section of my contract and the particular pitfalls I’ve encountered along the way. Hopefully it will give you a general idea of what to look for when dealing with photographers and help you understand how changes to contracts can affect the final price you pay for the images.

How can I use this image?

One of the first things I tell my clients is how my photos can be used. I could permit my images to be used in print but not online or I could allow clients to use my photos for editorial projects but not advertising. The way the images are used can affect how much I charge. For instance, using an image on a run of 5,000 flyers won’t cost the same as using it on a run of 100,000 magazines.

How many times can I use this image?

This section of my contract sometimes causes confusion because clients are unsure how it differs from the section before it. Using the magazine example, they wonder if 100,000 magazines constitutes one usage or 100,000 usages. To make it easier to understand, I tell my clients to think of a usage as a project. When I say that they can use an image 15 times, what I mean is that they can use that image on 15 different projects. Note: Not all photographers define their terms the same way I do. Always make sure you understand their contracts before signing on.

Where can I use this image?

Many professional photographers make the bulk of their income from image licenses; not from the “photographer’s rate” or “day rate” they charge to actually shoot those images. That means granting different licenses in different geographic regions helps them to boost their bottom line. For instance, I shoot photos for a Canadian-based NGO that works with rural Peruvians. If I granted them an exclusive license for North America on a set of images, I could still grant a UK based non-profit an exclusive license for Europe on those same images. Understanding where you need to use your images can help you lower the cost of photography (as a license for one continent or country should cost less than worldwide usage). Note: Be sure to ask your photographer how they treat the Internet when it comes to geographic license.

When can I use this image?

The final piece of information I always put on my contracts is when the image can be used. In this section I tell my clients how long their license is good for. It can be as short as a few days, as long as several years, or even perpetual (if they pay enough). This section could also tell my clients if there was a date they could not use the image before, as in the case of an embargo. Which brings me to…

Other notes

This final part of the license section on my contract is where I can add any number of extra privileges or conditions. I’ll run down a list of some common items that might appear here.

Exclusivity: If I grant an exclusive license to the client, that means I can’t sell those images to someone else. Often exclusive licenses will include a caveat that allows me to use the images in my portfolio, blog, etc. Embargo: Often a client doesn’t need (or can’t afford) an exclusive license. In that case they might ask for an embargo. This allows them to use the images first — before I post them on my portfolio or sell them to someone else — but doesn’t cost as much as an exclusive license. Transferable Rights: One NGO I worked with was closely associated with a sustainable travel company. They wanted to know if the images I shot for them could also be used to promote that company (i.e. were the rights transferable). I could have granted the NGO transferable rights but together we decided it would be easier to come up with a separate contract for each organization.

In closing

I know, I know, for a busy and growing NGO — especially one without a full-time media manager — photographic licenses can seem complicated. Unfortunately there isn’t a standard contract in this industry though efforts have been made to homogenize the terms.

However, I think a well written contract, one that covers all the concepts mentioned above, offers a great advantage to both photographers and their clients. It lets NGO’s know exactly what they are getting and won’t leave them wondering how they can use the delivered images.

If you want to dive deeper into this issue, I highly recommend John Harrington’s book “Best Business Practices for Photographers.” It is written to photographers but offers helpful insight and resources to anyone who deals with photography contracts.