Becky Warnock: The Influence of Colonization on Images of Africa

Becky Warnock is an artist, facilitator and activist. Her artistic practice crosses photography, film, and theatre. She uses participatory practice to engage with the people she works with. Her focus is on creating innovative, community engaged art powered for social change. She trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama and studied for an MA in Documentary Photography and Photojournalism at London College of Communication, which allowed her to also work at PhotoVoice as one of the Projects Managers. This furthered her commitment to developing a participatory practice and using the arts for social change and ethical photography.

Hi Becky! Thanks again for agreeing to be interviewed. Can you tell us what motivated you to do your MA project, called "The Colonized Eye," on how colonization affects visual representations of Africa?

Thanks for interviewing me!

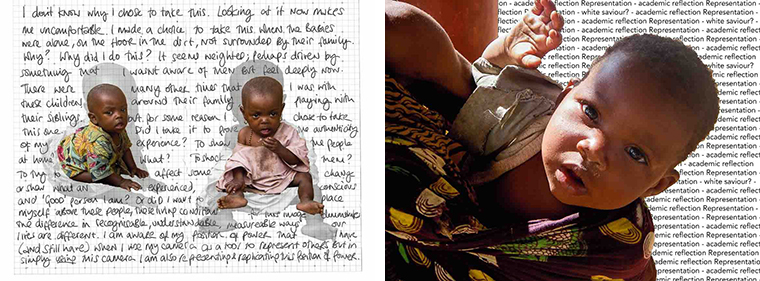

It’s an area I had been interested in for a while. I regularly think about the NGO imagery on the tubes or in adverts. As a white, middle-class, British woman, my cultural identity has been shaped by a patriarchal, white-dominant society seeking to oppress other perspectives and understandings by actively denying our colonial history. Using images I took ten years ago as stimulus, I tried to reflect on my naivety and question my internalized prejudices from my background.

Through my previous work with charities and international development organizations, I gained an increased understanding and critical awareness of the politics of representation. It is easy to reflect on an academic theory without considering its application in everyday life on a personal level. I wanted to critically consider my position within the complex concepts I was researching – in some ways it was a process of visually ‘checking’ my privilege. The project is the unpacking of the images, influences and politics that contribute to my current understanding. I’m sure over time this will develop and change, just as my own position will.

Currently, my project exists only as a bespoke 'deconstructed' book. I designed it so the viewer had a choice about how to interact with its contents. It can be read in any order and it combines different paper types and formats. I’m in the process of working out how to digitize it, so it will be on my website in the next few weeks. I’m also hoping to make it into an installation at some point, but that might need to wait till I can find some funding.

Your project focuses on a collection of photographs you took while volunteer teaching when you were eighteen years old. Can you tell us about the trip and the kind of images you created?

I was volunteering to teach English in a remote village in the Usambara mountains in Tanzania. I was there for 4 months, and though it wasn’t my first trip to Sub-Saharan Africa, it was formative in my perception of the continent. I wasn’t particularly interested in photography at the time. So the images I took were just a way of documenting my experiences.

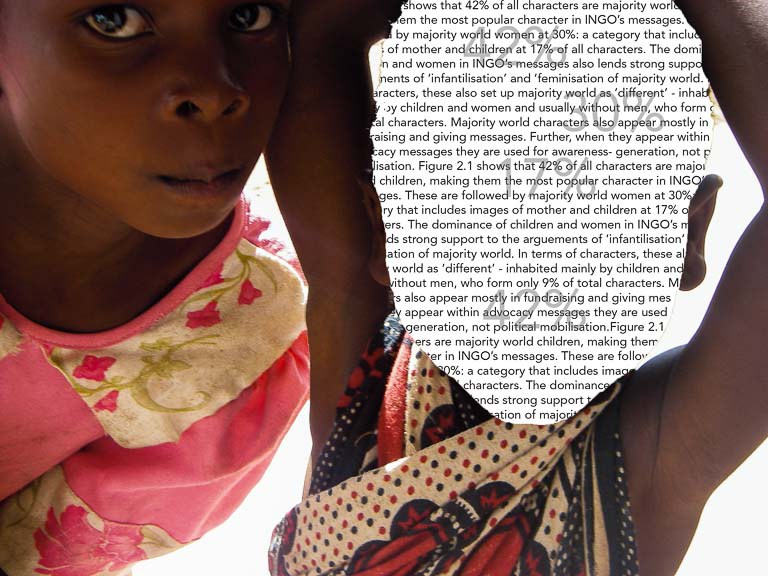

When I look at them now I view them in a different light. You can see the influence of the NGO imagery that I had seen at home. I did things like take photographs of children, images of things that seemed exotic, and images of poverty. My images at the time seem to focus on visible signs of depravation such as worn clothing, dirty environments, or rural tasks that could appear ‘backward’ from modern technology.

I don’t believe that I was consciously ignoring other images that I saw. But my gaze was seeking out these representations as a way of authenticating my experiences. Similar to the recent controversy that Steve McCurry had photoshopped his images to remove lamp posts and road signs in his images of Cuba and rural India – I was interested in the idea that I had chosen to focus my image making on the aesthetics of poverty.

What is the significance of the faces/people/backgrounds cut out of the photographs and the words placed in those cut-out spaces?

I wanted to confront myself and the viewer with images that were seemingly familiar, but to re-engage with them in a different way, surrounded by the research and questions that I had asked myself. I hope this will potentially encourage the viewer to do the same.

What perspectives shaped the work? What things do you think commonly influence other people to take these kind of photos when documenting life in a place different from their own?

I think that most people are well intended. On the whole, professional photojournalists on assignment are looking to tell a story or document the work of an NGO. Tourists often just want to share their experience. The issues come about when the images are used as a single narrative of events, and when they are decontextualized from world politics and an understanding of the concepts of representation.

Images that are used for fundraising purposes are particularly difficult to negotiate, as there is a tension between the need for images that elicit a direct response – or generate money – and those that perhaps show a more nuanced reality. Unfortunately, it seems that NGOs believe images that shock an audience generate more income, and as such, they dominate nonprofit publications. The Rusty Radiator website is a great place to see examples of this internationally. There is research to substantiate this argument, but despite awareness of the potential negative long-term effects of this imagery in the interviews I conducted with NGO workers for this project it still seems to be difficult for fundraising teams to risk poor donation rates on a campaign, so few are able to trial more positive campaigns.

Recently more charities are starting to bring positive imagery into their fundraising efforts. HIV and AIDS Alliance’s “Love a Positive Life” is a great example. However, the dominance of imagery from African nations in NGO fundraising calls can be seen to generate a ‘white savior’ narrative, which manifests in depictions of western celebrities surrounded by adoring children, white NGO workers providing disaster relief, or fundraising campaigns that claim donating £1 will make all the difference. The white savior narrative is particularly problematic in a European context, as it negates acknowledging our colonial role in the history of African nations.

I hear the phrase ‘giving someone a voice’ a lot, as a way of encapsulating a desire to support others in a campaign or run a project about representation, but for me, this idea is wrong. People have voices, the problem is more that those in power aren’t listening.

What have you learned by reflecting these images and diving into research about colonialization? What would you change now if you were in a similar situation?

One of the things I noticed when I started reflecting was how western-centric my perception was. I tried to play with this by opening my project with an image of a lion, which is an image of strength, pride, and African culture, but also epitomizes colonial rule, having been appropriated and used as the image of British monarchy and power. For me this is the embodiment of our current understanding of African culture: only shaped through our own understanding and popular representations in western mainstream cultures and too often flawed by institutionally racist undertones and issues of cultural appropriation and exoticism.

For this project I tried to immerse myself in writing and theory from other cultures, and see how this contributed to my process. I read a lot of Franz Fanon, Stuart Hall and this article by Kenyan writer Binyvanga Wainaina became the centerpoint for my work. This process was important for me, but I found myself returning to the quote by Plato ‘Those who tell the stories also hold the power’. The concept resonates within my own practice as a participatory artist and I think will continue to be central to my practice.

You mention that on a recent trip to Rwanda you were unable to reconcile what you’ve learned about colonialization with taking pictures during your trip. Do you think you’ll ever be able to get back into this kind of work? Why/Why not?

Yes that was interesting! In developing this project, I had hoped to create new work during my recent trip to Rwanda. I found myself bound by ethical considerations from which I was unable to disentangle. I felt hyper aware of the power I hold as a white British middle-class artist. It was at this point as I described previously, I found myself returning to Plato’s words. It is ironic, in a work in which I have attempted to deconstruct my own gaze as colonial and instead attempt to introduce more African academics, writers and thinkers and their view points, that I should return to a white man seen as one of the forefathers of western society.

Whilst I cannot control the socio-political historical factors that I carry as a western, white, female photographer, as the writer and visual culture critic Ariella Azoulay says, I can assert my “right not to be a perpetrator”. I think I will make images again the next time I travel, but perhaps in a different way. I think I will be more conscious of this in planning for my projects- trying to find ways of embedding my participatory practice not just in the way I make images, but also in how they are used and in deciding what they are made for.

What advice do you have for media makers and organizations who want to create dignified, respectful photography to address complicated issues. Are there ways to address the distribution of power between photographer and subject?

I think we have to try and counteract the white savior narrative, and stop viewing people as victims. David Campbell talks about a need to “move from singular expression to collective action” in regard to image making. He argues that we need to stop creating images that view African (or other majority world) countries as ‘in need’ and consider what interventions are already happening and what still needs to be done. The action he describes perhaps being an increased political awareness, not just of others, but also our own individual positions.

I hear the phrase ‘giving someone a voice’ a lot, as a way of encapsulating a desire to support others in a campaign or run a project about representation, but for me, this idea is wrong. People have voices, the problem is more that those in power aren’t listening. It implies that we have the power to distribute ‘a voice’ which in turn implies that we can take it away. I think we need to redirect the intentions of these projects or campaigns to amplifying the voices of those affected towards those who are able to make policy level change, and challenge ourselves and our peers to consider our own role within that process.